3. Two Obituaries Considered

"The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here..."

The North American obituary of Robert Neilson was, in effect, a thorough, highly sympathetic biographical sketch of the man. It elaborated upon the spare treatment of the life of “Colonel Neilson” offered ten days before in the Inquirer, piling elegiac sanctifications on that first, brief account of the man. The clipped, allusive tone of the Inquirer piece yielded to a fuller, more generous, almost hagiographic account of Robert Neilson’s nearly 86 years on earth in the North American.

The North American provided not just a summary of milestones and achievements; it gave also an approving measure of the man—his disposition and temperament. Was he not “well known and estimable”? Did he not possess a “vigorous intellect” and “uprightness of character”? Did his “ability, love of justice, prudence and courage” not command “the universal confidence and respect” of his contemporaries and peers?

Was he not modest? In 1836, having “left Trinidad and retired,” Robert Neilson would have been 55 years old, “with an ample fortune.” He had distinguished himself sufficiently to be “gazetted for his faithful and efficient services…‘Right Honorable’,” yet he was too self-effacing to go around calling himself that. His brief residence in Canada provided additional evidence of humility in his refusal of an appointment to the “Queen’s Council.” What cared Robert Neilson for the trappings and distinctions of office?

Was he not honorable? Robert Neilson’s fellow Trinidadians placed their trust in him in so many ways! “Puisne Judge”! “Member of the Executive Council”! “Command of a colonial regiment”! When he moved to Philadelphia for good in 1838, Robert Neilson did not seek to become a naturalized U.S. citizen—his service to the British Empire and the Crown’s manifest gratitude influenced “his sense of the proprieties of his position.”

Even as Robert Neilson and his family established themselves in their new home, eminences in Whitehall continued to consult him. The correspondent explained, with implicit confidentiality, that “relations of Mr. Neilson with the heads of the British government have been of the most intimate character.” Not quite at liberty to relate what was discussed, presumably, the obituarist here sewed up the matter by assuring the reader that “whatever political information [British officials] sought of him was given in a liberal spirit, and in the sense best calculated to promote the friendship and well-being of both countries.” Robert Neilson was very well connected; important personages of the British Empire sought his advice regularly. And he responded with integrity and discretion.

Perhaps most important, given the place and time, Robert Neilson was a Union man all the way, despite his bonds to the British Empire. Two of his sons had fought under the Stars and Stripes, one giving “the last full measure of devotion,” as Lincoln had it at Gettysburg. Robert and Emma Neilson had made the parents’ ultimate sacrifice just months before the end of the War for that “new birth of freedom,” in a fight that was somehow trying “the proposition that all men are created equal.”

As the North American remembrance tacked home, readers were once more reminded of the “modest and retired habits of life” that caused Robert Neilson to ignore “his early titles, as well civil as military.” This return once again by the North American eulogist to the matter of titles seems designed to erase the implication in the Inquirer notice that referred to Robert Neilson as “Colonel” fully three times in a single short paragraph.

The Inquirer obituary had an opacity and a formality, the curt chill of which was not entirely relieved by the assurance in the final line that Colonel Neilson was “greatly beloved and esteemed by the large circle of friends and relatives who knew his worth.” Colonel Neilson may have seemed a man of stiff, martial formality, the notice seemed to say, but you would have liked him if you’d gotten to know him.

The North American piece, on the other hand, published a full two weeks after Robert Neilson’s death, twelve days after his funeral, and nine days after the article in the Inquirer, reads like a corrective. Even late in life, when sorrows came “not single spies, but in battalions” and losses had fallen heavily upon him, Robert Neilson was “a most interesting and instructive companion,” and in a final wind-up, the obituarist pronounced him, “Of noble presence, kindly temperament, and genial manners.” Praise his “liberal heart and hand”! “[H]e lived greatly esteemed, and died sincerely regretted by all who knew him.”

Just so. Two Robert Neilsons now emerge from the shadows of the past. The February 7th Robert Neilson of the Philadelphia Inquirer stands stiffly: a formal and flinty man who insisted on the nominal dignity of a military title (“Colonel…Colonel…Colonel”) conferred in a long ago time and place. The second Robert Neilson, presented on February 16th in the North American is more of a warmly remembered pater familias, generous, discerning, and engaged to the last. He wears carpet slippers and invites warm companionship.

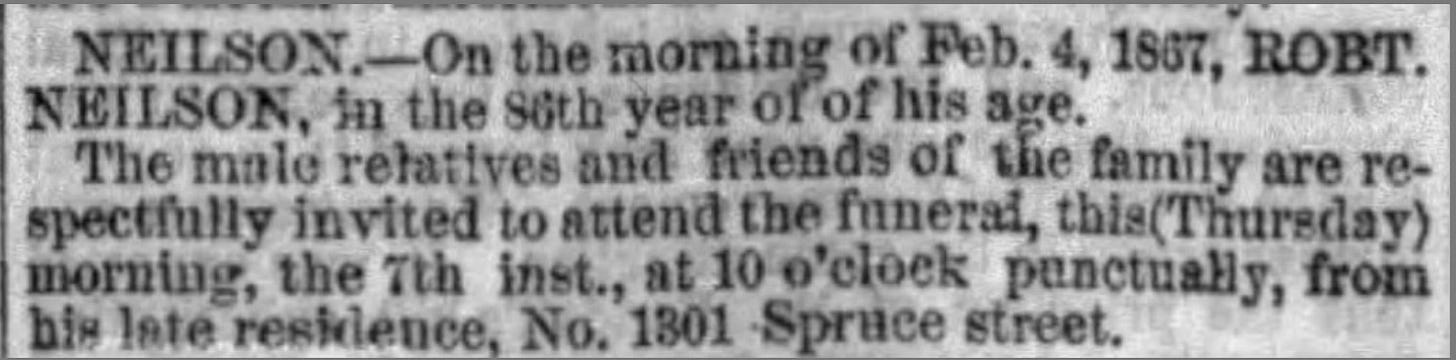

After friends and family had gathered at 1301 Spruce Street, possibly at Robert Neilson’s very funeral with the Inquirer obituary sitting on the center table with a cracked marble top in the parlor, a strategy may have emerged for remaking the impression created by the Inquirer’s first draft of the man. Was Morton McMichael with William D. Lewis there to pay his respects? So much the better! They would have planned how Robert Neilson’s lasting reputation might be reframed to comport more with the real man—either as they knew him, or as they wished him to be remembered. The author of the second, longer obituary—Robert’s son Thomas?—clearly wanted to emphasize Robert Neilson’s many accomplishments rooted in personal virtues, along with bracing perspicacity and lack of pretense.

The debt that the writer of the North American piece owes to the possibly unsatisfactory prior notice in the Philadelphia Inquirer can be glimpsed in a direct comparison of the final lines of each. The basic structure of the first sticks out like a pentimento in the second—evidence, perhaps, that the sympathetic eulogist writing in the North American presumed that he was improving on the bare bones of the first:

Philadelphia Inquirer, February 7, 1867:

He was a gentleman of much culture, and greatly beloved and esteemed by the large circle of friends and relatives who knew his worth.

North American, February 16, 1867:

Of noble presence, kindly temperament, and genial manners, and to all those about him of liberal heart and hand, he lived greatly esteemed, and died sincerely regretted by all who knew him.

And for his descendants in the present era—the early 2020s that will one day assume a similar quality of opacity to descendants yet unborn—there are important leads and questions for further inquiry:

What was the nature of Robert Neilson’s early life in Ireland? Where exactly was he born, and why did he leave? Did he convert to Anglicanism during this time, or was he Church of Ireland born? Exactly which of His Majesty’s services did he join, and what did he experience, once in it?

What did Robert Neilson’s activities “as a merchant and planter” in Trinidad entail? How was it that he “retired” from his life there “with an ample fortune”? What did his colonial service entail in practical terms (“‘puisne Judge’,” “Executive Council,” military service and command)? What exactly did he do to be “gazetted (‘Right Honorable’)…for his faithful and efficient service”?

How did Robert Neilson spend his two years in Upper Canada (later known as Ontario)? Why did he leave? Why did he then proceed to Philadelphia?

Notwithstanding his “singularly modest and retired habits of life,” how did Robert Neilson spend his remaining nearly thirty years in Philadelphia? How did the many children who established roots there with him make their way in the world? And what of his one child, Eliza (his second daughter), who did not join the family in Philadelphia? What became of her?

And how did Robert Neilson, “his long-cherished wife” Emma, and the rest of his family take the loss of one of their own in the Civil War fight to preserve the Union and destroy slavery? How did Robert Neilson feel as the War came to an end, his wife died, and he contemplated the end of his own long life—all within two years? How did he grieve, and who was with him at the last?

Who exactly was this Robert Neilson? Was he the February 7th or the February 16th version? Or some other version entirely?

Sources

“Death of Colonel Robert Neilson.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 6, 1867.

“The Gettysburg Address.” Abraham Lincoln presented at the Dedication of the Gettysburg Battlefield Cemetary, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, November 19, 1863.

“The Late Robert Neilson, Esq.” The North American & United States Gazette, February 16, 1867.

The Philadelphia Inquirer. “Funeral Notice: Neilson.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 7, 1867.

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth.

Just so, so good — there's no other way to say it!

I’ve dug in here, interesting! Thanks Jamie.