I became interested in family history gradually, during a time when I was busy with a great many other things. This was twenty years ago or more, when I was working as a teacher of literature and history, as well as a school administrator. I was married with two young children. What I learned about my family’s past came in idle moments, with the help of the Internet, which was at that time becoming an essential tool in many domains, not the least of which was stalking the past.

My brother, sisters, and I didn’t have a lot of hard information about our family that stretched back more than a generation or two. Our father had lost his parents early. His mother when he was not yet two months old, and his father when he was eleven. What we got from him about family history on his side was mostly anecdote and lore: tales of “characters” seen through the eyes of a small boy. Dad always emphasized that in the absence of parents, he was raised by a wide circle of adults who loved him very much—his older brothers, Hank and Albie, his teachers, his Aunt Gigs, his grandmother—known as “the High Command”—a nurse nicknamed Brow, and finally, Chester Stanley. Chet was a Maine lobsterman who managed the High Command’s boats in the summer, took care of her grandsons, and over time became their surrogate father.

Our father gained much from these relationships. He lived in a comfortable world of nicknames, funny stories about oddballs and eccentrics, and infinitely repeated witticisms. I got the sense that the adults in his life, especially the ones who were related to him, spent a lot of time goofing around and entertaining him. He was often in the company of the High Command. Clara Neilson was a great story-teller, and our dad heard many colorful yarns about her family, the Rosengartens, who ran a successful medical compounding company in the 19th century. Many of these tales, Dad passed along to us.

His Neilson grandfather—our great grandfather—was known as Joe Duke the Iron Brakeman. He’d been the Secretary to the Board of Directors of the Pennsylvania Railroad (“the PRR”), which was among the largest corporations—if not the largest—in the country and in the world in the late 19th century. Lewis Neilson’s family nickname made squinting reference to that career and, perhaps, to the American fetish for the folklore of working men and railroad progress. Lewis Neilson was no Paul Bunyan or John Henry. He’d felled no trees, pounded no spikes, nor had he pulled any locomotive’s brake. He’d been a pencil-pusher, albeit an important and prolific one: leap-frogging clerkships in the PRR for some twenty years starting in June of 1881. Arriving at the bureaucratic pinnacle, secretary to the PRR’s corporate board in 1901, Joe Duke maintained the minutes of meetings, notarized and witnessed the contracts, and affixed his name each year to the preprinted envelopes for proxy votes. In 1925, the Philadelphia Inquirer enthused of my great grandfather that “Nobody else in Pennsylvania, or perhaps in the world, can compete with him in this business of secretarying,” owing to his status as secretary of 96 corporations (though the reporter acknowledged not knowing the names of the other 95).

Another of Joe Duke’s nicknames was “the Remains,” which commemorated his tendency to complain as if he were about to die. Long after their grandfather’s actual death, my father and his brothers would wheeze out imitations of his complaints about “the ice water breeze” in the Great State of Maine—a place that my father and uncles loved, but that Joe Duke allegedly deplored. In home movies from the 1940’s, he appeared briefly and mostly inertly—usually reading a newspaper and never playing with any of the little boys capering in the foreground. I gathered that his disposition was…how to put it? Sedentary and sort of plaintive. The “iron” was irony, and you wouldn’t have wanted to rely on him to stop any train that carried you or your loved ones.

The contrast between our father’s grandparents led to the family shibboleth that the Neilsons of the present day owed their charisma and gift of gab—for surely they had these!—to their Rosengarten forbears. Lewis Neilson was as far back as it went for my siblings and me. He stood at the end of a respectable, but also colorless and kind of stuffy, line. When we began to get curious about family history on the Neilson side, we were told that there’d been some doctors back there and a summer home in New Jersey, before Joe Duke’s job with the PRR—and the access to private cars that went with it—put Maine within reach. Elsewhere up the tree, someone had died in the Civil War, and someone else had made off with a lot of money belonging to the Mask and Wig, the musical theatre outfit at the University of Pennsylvania. And way back across the years, a colonial governor…of Trinidad maybe, but who could be sure?

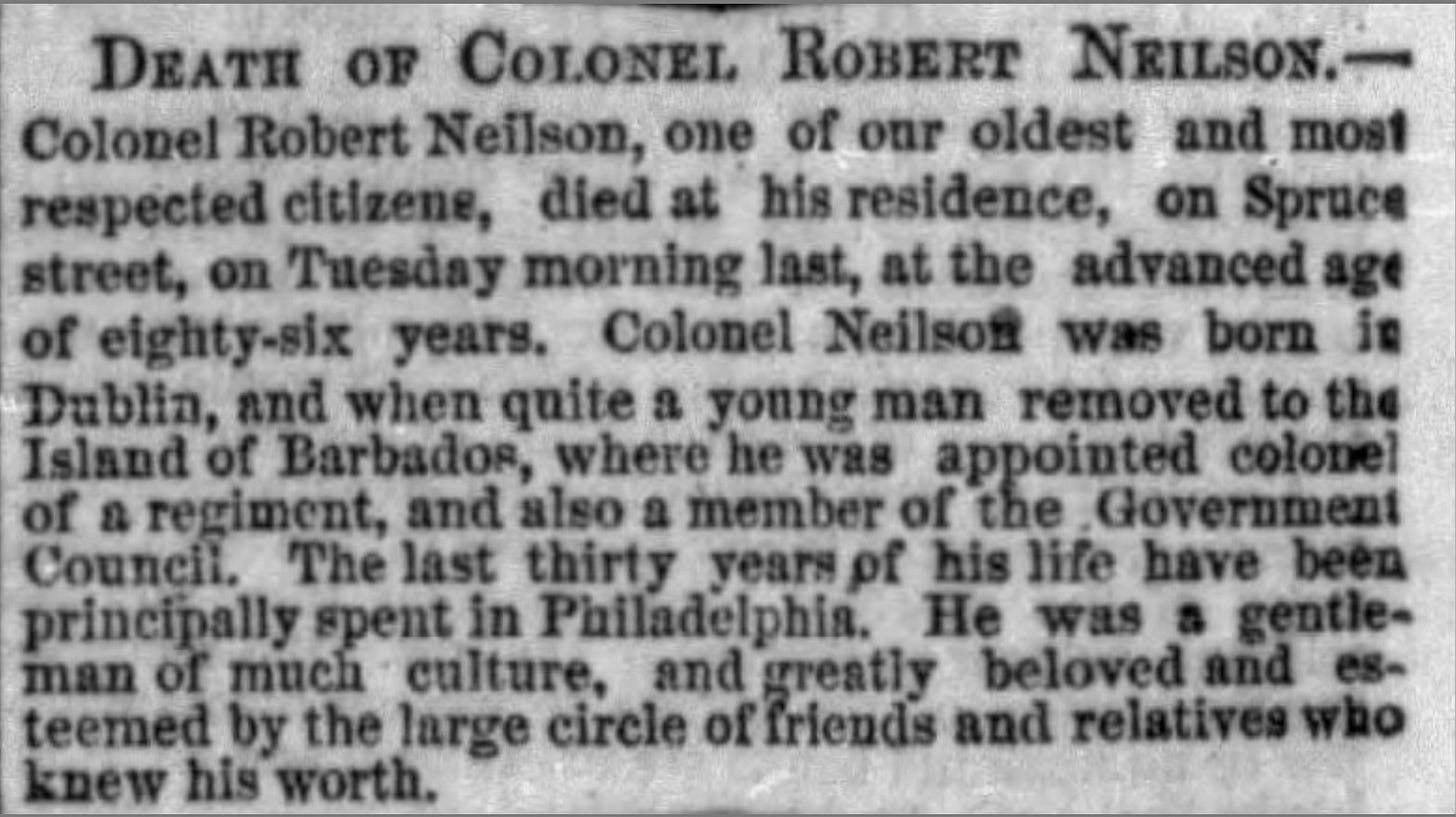

As I became fitfully engaged with family history, I wanted to reach back as far as I could, and this guy from maybe-Trinidad seemed to be the best bet. Somewhere in there I came up with a name: Robert Neilson. Increasingly, searching the Internet yielded surprising results on a whole variety of diverse topics, especially if there were likely to have appeared in the paper. One day, when I should have been doing something else probably, I went around and around on Google until I came up with this, from the February 7, 1867 edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer:

I would later learn that the short piece was shot through with errors. But at the time it offered tantalizing knots of specificity: “[A] colonel of a regiment in Barbados”? What did that entail? And what of the “Government Council”? Where on Spruce Street? If he’d been in Philadelphia for thirty years, then he must have arrived there in the mid-1830s. That he was “greatly beloved and esteemed by the large circle of friends and relatives who knew his worth” seemed somehow to affirm something important, something I wanted to believe about myself and my family in the present. It seemed like fulsome praise, but also just an assurance that the Colonel had been well liked. Sure, the obit was brief, but that felt like old “Colonel Neilson” was late and lamented.

Didn’t it?

Sources:

“Death of Colonel Robert Neilson.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, February 6, 1867.

“Ends Long P.R.R. Service.” The New York Times, October 2, 1930.

“Girard’s Talk of the Day,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, November 28, 1928.