Soon after making my earliest discovery, I joined Ancestry.com. For a fee, you could use an ever-growing menu of search tools to locate primary source documents, often piggybacking on the work of others who had already made extensive family trees that were viewable to subscribers on the service. Ancestry.com provided an unimaginably vast trove of materials, but I still didn’t have the time or the patience to use it to its fullest potential. Still, I was able to begin fleshing out some more basic information about the Neilsons of the 19th century.

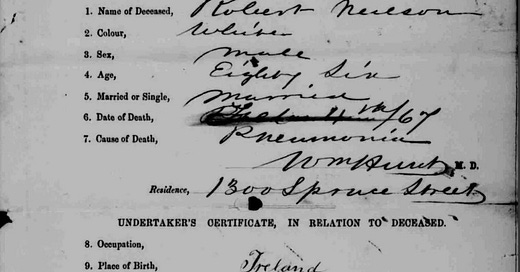

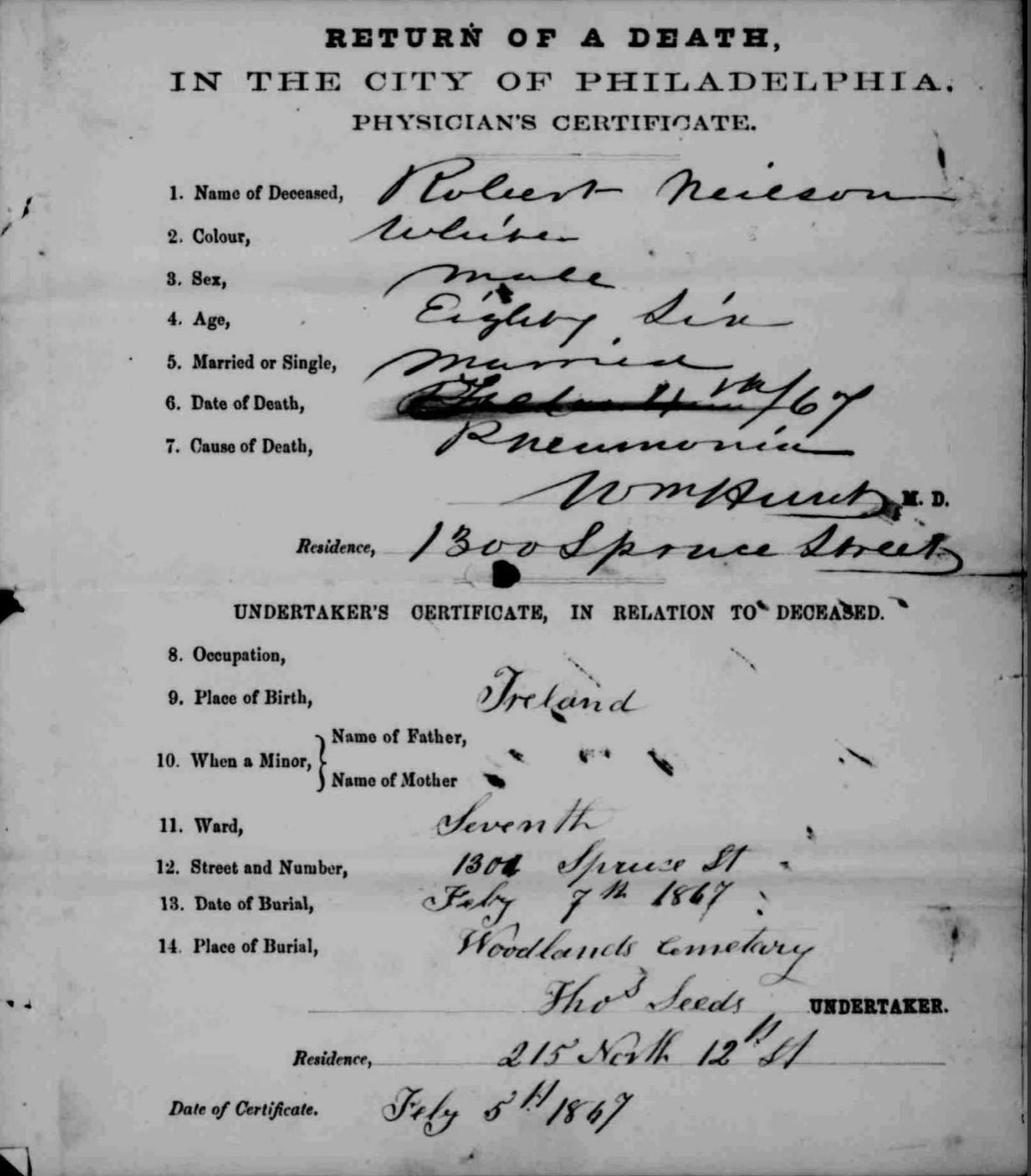

Ancestry yielded an important early clue—Robert Neilson’s “Return of a Death,” or death certificate from the City of Philadelphia. This document confirmed several basic facts and added a few new ones:

The document fixed Robert Neilson’s age—“Eighty Six”—at the time of his death establishing that he’d likely been born in 1781.

His place of birth was Ireland.

Robert Neilson appeared to have died at home, and the cause of death was pneumonia.

His address in Philadelphia at the time of his death was 1300 or 1301 Spruce Street.

But something else that I found in another corner of the Internet provided leads to exploring the deeper question of who Robert Neilson was. A second obituary, this one printed in the North American & United States Gazette on February 16, 1867, almost two weeks after his death:

The Late Robert Neilson, Esq.

The above-named well known and estimable gentleman departed this life on Monday, the 4th inst., near the close of his eighty sixth year.

Mr. Neilson was a native of Ireland, which he left in his early manhood for the West Indies, attached to the commissariat [sic] department of the British army, and was present at the capture of Martinique from the French, in 1809. Having concluded to devote himself to commercial pursuits, he resigned his military position, and, after a short sojourn at Barbados, removed to Port of Spain, Trinidad, where he established himself as a merchant and planter, and where he married, with a view of making it his permanent home. Here his vigorous intellect and the uprightness of his character soon attracted the notice of the colonial government, in which it was not long before he was called to take part.

The affairs of that important colony, the largest and most valuable, except Jamaica, of all the British West India islands, were administered by a Lieutenant Governor and an Executive and Legislative Council. With no trial by jury, and its legislature composed of a mixture of Spanish and French laws, at the period referred to, much wisdom was required in its government, as well as to uphold the rights of the Crown as to satisfy the wants and wishes of the people. It was under such circumstances that Mr. Neilson was appointed a “puisne Judge” and member of the Executive Council, whilst holding at the same time the command of a colonial regiment, and it is but simple justice to say that, both as an expounder and enforcer of the laws, his ability, love of justice, prudence and courage, commanded the universal confidence and respect of the inhabitants, as well as of his colleagues and of the home government.

In the year of 1836, when Mr. Neilson left Trinidad, and retired, with an ample fortune, to reside for a time in Upper Canada, the British government gazetted him for his faithful and efficient services and authorized the prefix to his name of “Right Honorable,” a distinction which his modesty prevented him from assuming, as in like manner he afterwards declined being made a member of the Queen’s Council in Canada. After remaining there about two years, he at length concluded to pass the rest of his days in the United States, where, with his family, he took up residence in 1838. Ever since then he has lived in this city, enjoying universal respect.

Although his sense of the proprieties of his position, having held office under and been honored by the British Crown, prevented him from becoming an American citizen, he had no sympathy with the rebellion, in opposition to which two of his sons took up arms, one of whom was severely wounded, and the other slain at the head of his command, whilst nobly defending the integrity of our government.

It is known to the writer that the relations of Mr. Neilson with the heads of the British government have been of the most intimate character, and we may feel assured that whatever political information they sought of him was given in a liberal spirit, and the sense best calculated to promote the friendship and well-being of both countries.

Singularly modest and retired in his habits of life, Mr. Neilson studiously ignored his early titles, as well civil as military, and avoided all effort to become prominent in the city of his adoption.

The last two years of his life were embittered by that heaviest of domestic sorrows, the loss of his long-cherished wife—the mother of his children—from which blow he never fully recovered. But even after dampened spirits and failing health had quenched much of the natural ardor of his character, he continued till near the close of his life to be a most interesting and instructive companion. Of noble presence, kindly temperament, and genial manners, and to all those about him of liberal heart and hand, he lived greatly esteemed, and died sincerely regretted by all who knew him.

The North American was a Republican paper published and edited by Morton McMichael. By 1867, it was anti-slavery, aligned with principles of Radical Reconstruction, suspicious of President Johnson (who had been thrust into office by the assassination of Lincoln), and, as it had ever and overwhelmingly been, pro-business. Robert L. Bloom quotes a city directory of 1858 that called the paper, “the recognized exponent of the commercial interests of Philadelphia” (170), and the Philadelphia Times, a contemporary competitor, that described the North American as “the respected organ of business in Philadelphia” (173). The North American would have been the sort of journal in which a sober-minded man of business—a man, presumably, like Robert Neilson—would have wished to have his final civic eulogy appear.

The question of the social and political orientation of Morton McMichael and his North American and United States Gazette becomes important for this very aspect of reciprocal regard: Robert Neilson’s family thought enough of the paper to have wanted it to publish an extended remembrance of their patriarch, and Morton McMichael held sufficient esteem for Robert Neilson that he was willing to comply. The North American had been pro-Union in the years before and during the Civil War because Unionism was good for business. McMichael had begun his political life as a Jacksonian Democrat, but he migrated to the Whig cause over his support for high tariffs. He was a key organizer of the first national convention of the Whig Party, the brainchild of Henry Clay, in Harrisburg, PA in 1839. Though he favored Henry Clay at the convention, McMichael strongly supported the eventual Whig Party nominees, William Henry Harrison and John Tyler, in the general election. The North American established at this time a firm Whig perspective that it would sustain through the years as the Whigs morphed into the Republicans. In 1857, the North American came out for the Republican John Frémont against the Democrat James Buchanan, who ultimately prevailed for a last misbegotten presidential term before the Election of 1860 brought Abraham Lincoln (whom McMichael revered) and Civil War.

Still, the Republican antipathy toward slavery made McMichael uneasy. For him (as for many Northern businessmen), antislavery reeked of radicalism, abolition, and the likes of John Brown. Even in 1860, the North American was suggesting that the business community in Philadelphia had no interest in intervening on the question of slavery where it was practiced in the South, and cared only for fiscal responsibility (i.e., profits) over “sentiment.” It was the protectionist issue of high tariffs that bound McMichael most strongly to the Republican Party, and as the editor of the paper that spoke first for what drove the city’s economic engines, we may assume that he was aligned with other minds and wallets in the business community. Robert Neilson’s thinking may have run along these same lines, and how he viewed slavery may have tracked with McMichael’s thinking and the North American’s bent.

Bloom notes that, “When the test of war came in April, 1861…the North American stressed its devotion to the Union rather than any hostility to the South’s ‘peculiar institution’ [i.e., slavery]” (174). But McMichael was also a devoted supporter of the Republican Abraham Lincoln, and just over a year later, he was calling the Emancipation Proclamation “one of the most important documents ever issued by a President” (174). He seems to have come to accept and, finally, to support the principle that for the Union to endure, slavery had to be destroyed. Did businessmen in Philadelphia generally hold that view? Did Robert Neilson?

J.G. Rosengarten (whose niece Clara Rosengarten would become my father’s grandmother) would recall fifty years after Morton McMichael’s death that the editor participated in “frequent social meetings” at the home of William D. Lewis, a prominent Philadelphian who had been the Collector of the Custom in the Port of Philadelphia and a leading supporter of the Union during the Civil War. Lewis was the father-in-law of Thomas Neilson, Robert Neilson’s son. William D. Lewis had served as private secretary to Henry Clay when Clay traveled to Europe to negotiate the Treaty of Ghent after the War of 1812. A former Whig, McMichael was a great admirer of Clay. It may have been through this Lewis connection and the bonds of political fraternity that Robert Neilson came to know the editor and to cultivate an acquaintance. At the very least, the connection may have been how the Neilsons were able to place this lengthy obituary, evidently containing ample material from Thomas, and possibly written by him entirely.

The version of Robert Neilson’s life offered in the North American corrected some of the errors in the Inquirer piece from ten days before: Barbados became Trinidad, for instance. But it also introduced new omissions, exaggerations, and flights of fancy introduced as fact, some of which would persist in various forms for decades to come. More than this, the North American obituary opened new areas of inquiry, and these were now yoked to specifics in a way that my questions about Robert Neilson had not been before. I now had a number of places to start.

Sources:

Bloom, Robert L. “Morton McMichael’s 'North American'.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 77, no. 2 (April 1953): 164-180. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20088456.

Return of a Death in The City of Philadelphia: Physician’s Certificate. Ancestry.com, accessed November 21, 2023. https://www.ancestry.com/mediaui-viewer/tree/32519973/person/19470221183/media/466cc8af-9984-48d2-a1f4-303e37eda33c.

“The Late Robert Neilson, Esq..” The North American & United States Gazette, February 16, 1867.

Weigley, Russell F,. “The Border City in Civil War: 1854-1865.” In Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, 363-416. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1982.